Published Date: March 8th, 2022

The current pandemic has caused many of us to rethink much about the way we live our lives: remote working, supply chain management and shopping have become daily topics of conversation. Local shopping was de rigueur 100 years ago, but today Amazon seems well entrenched. What is the impact on our independent businesses? Restrictions are loosening but will we return to our old shopping habits or will reliance on our online options continue to grow? For those of us who wish to see independent businesses survive, it has never been so critical to support local shop owners by opening our pocketbooks as we walk through their doors.

Through our collaboration with the Westmount Historical Association, we invite you to step back in time to the early 20th century for a sense of what shopping might have meant for Montrealers who also knew what it meant to survive a pandemic. We’ll introduce you to a few of the Irish entrepreneurs who built fortunes catering to their shopping needs:

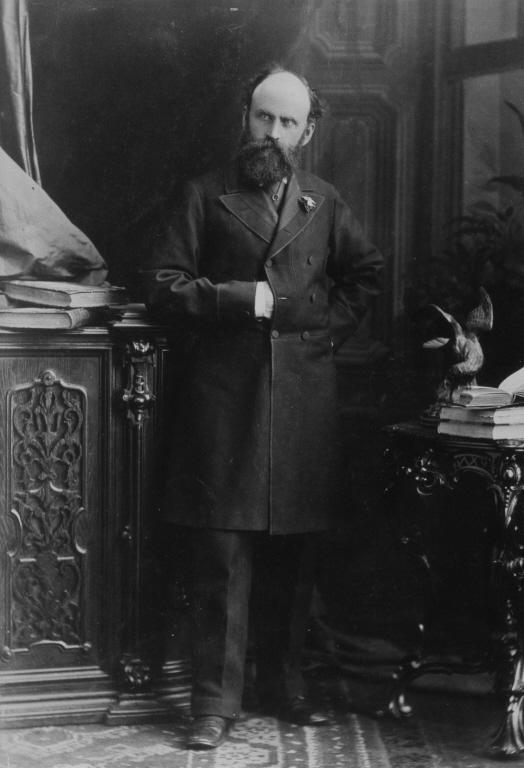

James McShane

As last month’s ICCC webinar featuring Charles Fallon clearly demonstrated, supply management is critical to the economic vitality of a city like Montreal. In the early 20th century, an Irish Montrealer was at the centre of that dynamic. Much of Montreal’s imported goods arrived by boat. Indeed, at the time, Montreal was the country’s most important port.

Born in Montreal in 1833, James McShane would cap off an illustrious business and political career as the city’s harbour master from 1900 to 1912. It was under McShane’s direction that elevators were erected to accommodate a growing grain trade and that the Montreal Harbour Commission acquired its own locomotives. James McShane was a member of the board of the Montreal General Hospital (1890–1917) and of the Shamrock Amateur Athletic Association, as well as vice-president of the St Patrick’s Society.

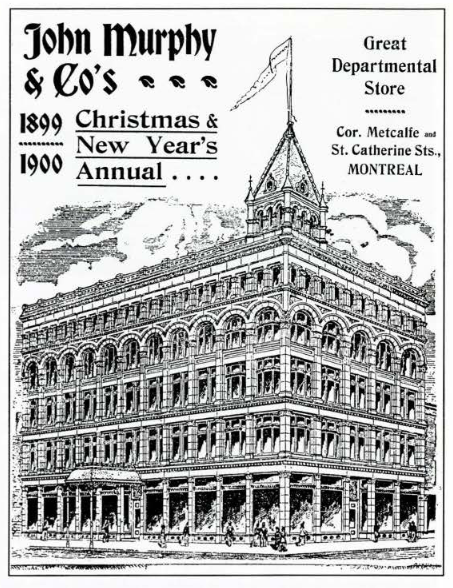

Murphy’s Montreal Shopping Centre

The son of Irish immigrants, John L. Murphy took over his family’s linen importing business with his brother in 1861. By the time he sold his Montreal holdings to Simpson’s in 1905, Murphy’s Shopping Centre was located in a five-storey red sandstone building at the corner of Sainte-Catherine and Metcalfe streets where La Maison Simons now stands.

Since demolished, the impressive building boasted a fire-proof interior, large plate-glass windows, elevator and centralized cash system. The location is telling, as the construction of major department stores such as Murphy’s, Ogilvy’s and Morgan’s (now La Baie d’Hudson) on Sainte-Catherine street signalled the end of an era in Montreal: retailers no longer needed proximity to wholesalers in the city’s lower-town. A location more likely to attract customers was now John Murphy’s prime consideration. Having divested himself of his Montreal shopping emporium, and now 70 years of age, John Murphy continued to advise the new management of his Ottawa location. During his long career as a merchant, this Irish Montrealer had made more than 100 ocean crossings to buy quality goods from European suppliers and fashion houses.

Robinson & Cleaver’s

Montreal households might have purchased Irish linen at Murphy’s or ordered it directly from Belfast’s Robinson & Cleaver. Whether “The Royal Irish Linen Warehouse” had a Montreal agent or simply advertised in the newspapers of the “colonies” such as the Gazette, remains unclear, but Robinson & Cleaver promised linen “made from the finest selected flax yarns and bleached by sun and dew”. The now-defunct company’s Belfast location, known as Cleaver House, remains one of the city’s iconic buildings. How many Westmount households still display its wares, one wonders?

ORAL HISTORY: DIANA MARTIN

SHOPPING LOCAL A CENTURY AGO

BY JAN FERGUS

First published in The Westmount Historian newsletter, vol. 21, no. 2, 46th edition, February 2021 (reprinted with kind permission from the Westmount Historical Association).

Most Westmount homes relied on deliveries 100 years ago. Diana Martin, who grew up here in the 1920s and 30s, has provided to the WHA many of her childhood memories, with the enthusiastic encouragement and help of her daughter in British Columbia, Wendy Hodges. Diana, at that time Wilson, describes among other things how goods were delivered to her house at 613 Belmont Avenue. Similar deliveries certainly took place at 178 Côte St. Antoine Road, as a surviving ledger among the Goode Fonds shows. But thanks to Diana, we can flesh out the ledger’s dry figures – because at age 96 and now in Toronto, she has recently written many lively, utterly engaging descriptions of her early life in Westmount. She sometimes actually illustrates what she remembers – as you can see in the page reproduced here.

“Shopping local” in 1929 meant that milk, bakery goods, ice, and above all coal were delivered by horse-drawn vehicles – and it was not easy, as Diana makes clear. Though her handwriting is wonderfully readable, here is a transcription of her words:

Horse-drawn ice wagon

One would put a cardboard sign in front window either 25 or 50 which indicated how large a block of ice was needed for the icebox. The ice box had: top was for ice, bottom for food, bottom pan for melting ice which had to [be] emptied regularly.

In winter milk was left between 2 back doors and the milk would freeze and cream would push the cardboard top up and we would eat the frozen cream. Our milk was in glass bottles delivered daily by milkmen.

Horse-drawn bakery wagon

Driver would come with large basket to kitchen door, full of bread and cookies and we’d buy what was needed. (Later was replaced by big truck.)

Horse-drawn coal delivery

Men would deliver coal to basement coal shuttle window – put coal in canvas bags and toss it over shoulder. They were very strong and did this until the coal bin was full. The whites of their eyes w[ere] very red from the coal dust!

The Ice Men also put large canvas over their shoulders as they heaved the big blocks of ice on their shoulders to the kitchen to the ice box w. tongs (and used tongs for lifting ice and then to fit it in ice box used ice picks to chip if it didn’t quite fit – we loved sucking the chips that fell. We were allowed to climb on the back of the wagon and eat slivers of ice.

Diana’s account of hauling, then heaving the sacks of coal down the chute sounds like very heavy work, and the detail of red eyes irritated by coal dust makes us really feel how tough that job was. Similarly vivid is the hard work of the ice men using giant tongs for the 25- or 50-pound ice blocks, with canvas to protect their shoulders, then having to chip the ice to fit the ice boxes. But Diana also conveys the delight that deliveries could bring to children, able to eat the frozen cream off the top of the milk bottles and permitted to suck the slivers of ice that collected in the iceman’s truck.

The Goode yearly ledger, kept by Harriet Ellen Goode from 1915-1929, reveals that at least the coal men didn’t have to worry about making their way over mounds of snow and ice in people’s yards during the worst of winter. Huge loads of coal for middle-class homes were delivered earlier in the year. And those deliveries could represent a large proportion of a family’s budget. For instance, in May, 1928 Harriet wrote a cheque to Vipond-Tolhurst Coal Company for $203.78, which represented nearly 8% of her meticulously calculated expenses of $2585.66 for the year. But a bad winter could wreck calculations, which happened in the previous year. In September 1927, $170.00 worth of coal was delivered, but in the following March of 1928, Harriet Goode bought another two tons of coal at $18.00 per ton.

Big purchases like the yearly coal delivery were paid for by cheque, but Harriet used cash in hand to pay for lesser items. In the same March of 1928 that she paid $36 cash for more coal, she also doled out a total of $20.61 to the butcher, $17.80 to the grocer, $5.43 for fruit and vegetables, $5.24 for flour and bread, and $2.32 for milk. Likely the bread and milk were delivered, and perhaps the groceries as well, possibly the meat too. Most of these are billed six or seven times a month, more than once a week on average, but milk just once a month. Harriet’s monthly expenses just for the “house,” as she puts it, came to $137.86 during this month. She usually had to top up her cash in hand every month by withdrawals of $100 from an account at the Royal Bank. Her other monthly spending categories included wages, chemist, dry goods, stationery, boots and shoes, electric light, travelling, and finally sundries – where the coal purchases appear. In other words, Harriet Goode seems well suited for a pandemic lockdown – much better than most of us were last March, 2020.

Again, although it’s not clear how many deliverymen came to 178 Côte St. Antoine, Diana Martin tells us that various irregular vendors made occasional visits to Belmont Avenue. They certainly came to the Goode house as well. The “umbrella man” repaired umbrellas and sharpened scissors and knives “and we would see with fascination the sparks fly from the grinder,” indigenous women sold handwoven baskets made of sweetgrass, and a “great favorite” was the pork and beans man: “delicious! The beans were in small round dark brown pottery jars and smelled wonderful! He too had his wooden cart which he pushed.” The WHA hopes to publish an article based on more of these fascinating memories in a future newsletter.

A former English professor, Jan Fergus is the coordinator of the WHA Oral History Project and a WHA board member.

IRISH MONTREAL’S TRAILBLAZERS

You can’t blame a man for trying. An entrepreneurially-minded Irish Montrealer, who wished to remain anonymous, posed the following question in the Montreal Star’s ‘Legal Queries’ feature on February 16th 1923:

“Is it legal to raffle a motor car, not for charity, solely for owner’s benefit?”

Sadly for them, the response was no.

Several Irish Montrealers have exemplified the entrepreneurial spirit throughout Montreal’s history. Whether they have remained anonymous, like the grocers, cobblers and icemen who certainly served Diana Martin’s Westmount, played a key role in the importing trade like James McShane, or built a shopping empire like John Murphy, you will continue to discover them through ICCC Montreal’s Trailblazers series. Stay tuned for more!

Michelle Sullivan of Michelle Sullivan Communications is Vice-President of the ICCC Montreal and Founder of HeSaidSheSaidStories.com and VosHistoires.com.